Diversification

25. Oktober 2023

What do the elections in Indonesia mean for the country as a de-risking destination?

Indonesia, the biggest balancer in ASEAN and the world’s largest supplier of nickel, just held its national election. Prabowo Subianto, the current defense minister, secured a landslide victory based on the promise to continue Joko “Jokowi” Widodo policies.

Indonesia’s “non-alignment” strategy and its rich mineral reserves have built the country’s attraction as a “China de-risking destination”. Will the new president challenge or improve that?

Key points from the report:

- “Non-alignment”: Prabowo will continue hedging efforts between the U.S. and China. Meanwhile, he wants to make Indonesia an influential power on the world stage. Prabowo will continue pursuing closer security ties with the U.S. despite frictions over his human rights record. His previous anti-China rhetoric and populist stance make him more unpredictable on territorial disputes, e.g. in the Natuna Sea.

- Trade diversification: Prabowo is less interested in diversifying at the cost of economic relations with China. He will continue engaging with China and other Asian partners to secure economic growth. While Prabowo will likely continue to push trade deals with the EU and U.S., his criticisms of “Western double standards” may complicate negotiations given the latter’s focus on ESG standards.

- Mineral policy: Prabowo vows to extend Jokowi’s “resource nationalist” strategy to more commodities beyond nickel, potentially banning their export and requiring foreign investment in downstream sectors. But there is no other commodity where it holds a similar monopoly position.

- Sinolytics Advice: European policymakers need to be pragmatic when negotiating with Indonesia, keeping the potential geopolitical benefits of strong EU-Indonesia relations in mind. Multinational businesses should be aware of growing protectionism and the China footprint in the mineral sector. They can seek investment opportunities in the “downstream” sectors, position ESG smartly in public communication and continue monitoring policy and political risks.

Read the full report here.

Ex-general Prabowo wins landslide victory

On February 14, around 205 million Indonesians cast their votes in another high-stakes election of 2024. Despite expectations of a closely contested race, early counts revealed the current defense minister Prabowo Subianto (founder of Gerindra party) securing a landslide victory. This set aside pre-election concerns about a possible run-off.

Meanwhile, the ruling PDI-P party is set to gain more seats in the country’s legislative body, positioning itself as an opposition force. While the official results will be released in March, the initial outcome signifies a shift from a united to a divided government.

Prabowo’s win is largely based on the promise of continuing the economic policies of Joko “Jokowi” Widodo (affiliated with the PDI-P party) who delivered fast growth in the past decade. Widodo’s signature policies are not uncommon for a developing Asian economy: Offering raw materials and cheap labor in exchange for foreign investment and localizing industries. But these policies have come at a cost: pollution, social disparity, and strong dependencies on China.

Why you should care: Largest swing state, China plus 1, nickel and beyond

Geopolitics: Can Indonesia uphold its hedging strategy?

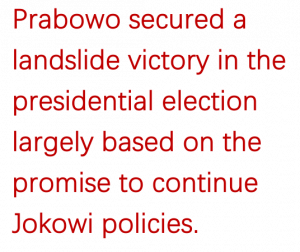

The Asia-Pacific is a key region of geopolitical contestation between China and the U.S. ASEAN, the Association of South East Asian Nations, is one of the most dynamic and fastest growing regions in the world. Collectively, the entire bloc of ASEAN economies are on track to becoming the world’s fourth largest economy by 2030.

Today Indonesia pursues a hedging strategy to maintain maximum flexibility between the U.S. and China.

As the largest country within ASEAN, Indonesia plays a key role and is viewed as a decisive driver of regional policy making. This makes it a pivotal partner for both China and the U.S. who curry Indonesia’s favor in the hopes of unlocking broader geopolitical influence in the region. As noted by former U.S. ambassador to Indonesia Robert Blake,“Indonesia is seen as being one of a handful of large swing states – along with countries like Brazil, Saudi Arabia, and India – who will have an important geopolitical influence globally if they choose to exercise it."

Similar to other countries in the region, Indonesia is pursuing a hedging strategy vis-à-vis the U.S. and China. Going beyond a non-alignment strategy, hedging is an active approach to court both sides and thereby maintain maximum flexibility. For Indonesia, the primary goal is to receive benefits from its biggest trade partner China without alienating the U.S. as an important security partner in the region. So far, Indonesia’s hedging strategy has been quite successful in maintaining equidistance between the two superpowers (see Sinolytics GeopolMAP to provide a systematic framework to assess relative closeness to U.S. and China based on 4 dimensions (economic, political, security, cultural). For further information on GeopolMap contact Martin Catarata.

Similar to other countries in the region, Indonesia is pursuing a hedging strategy vis-à-vis the U.S. and China. Going beyond a non-alignment strategy, hedging is an active approach to court both sides and thereby maintain maximum flexibility. For Indonesia, the primary goal is to receive benefits from its biggest trade partner China without alienating the U.S. as an important security partner in the region. So far, Indonesia’s hedging strategy has been quite successful in maintaining equidistance between the two superpowers (see Sinolytics GeopolMAP to provide a systematic framework to assess relative closeness to U.S. and China based on 4 dimensions (economic, political, security, cultural). For further information on GeopolMap contact Martin Catarata.

However, a Prabowo presidency, who expressed ambitions for his country to play a greater role internationally may adopt a more assertive geopolitical stance in the region or strive for a leadership role in the “Global South”. Will he be able to continue upholding Indonesia’s hedging strategy without upsetting either Beijing or Washington?

Trade: Will the West’s courtship draw Indonesia away from China?

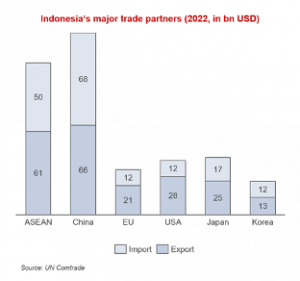

China is Indonesia’s most important economic partner. In 2022, Indonesia’s overall trade with China reached 134 bn USD (see graphic 2 below). The U.S. on the other hand lags far behind with overall trade of 40 bn USD with Indonesia.

Similarly, Chinese companies are more invested in Indonesia than their U.S. or European counterparts. This is partially driven by China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which encourages Chinese companies to finance and build large infrastructure projects in the country.  In fact, Indonesia is a priority country under the BRI. In 2015, Xi Jinping chose to launch China’s maritime Silk Road in Jakarta. Just last year, the Jakarta-Bandung High Speed Railway, a flagship project under the BRI, was opened jointly by Xi and Jokowi.

In fact, Indonesia is a priority country under the BRI. In 2015, Xi Jinping chose to launch China’s maritime Silk Road in Jakarta. Just last year, the Jakarta-Bandung High Speed Railway, a flagship project under the BRI, was opened jointly by Xi and Jokowi.

The U.S. and the EU have come up with a series of programs to accelerate economic diplomacy with Indonesia and incentivize the country to reduce dependencies on China. The Biden administration’s Indo-Pacific Strategy seeks to improve economic engagement with Indonesia through the Indo Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) and a potential critical raw material trade deal with Indonesia.

The U.S. and the EU accelerate their strategic engagement with China.

The EU also sees Indonesia as a potential partner for de-risking. The necessity to diversify supply chains has put new impetus behind a free trade deal between the EU and Indonesia that had remained stuck in negotiations since 2016. The EU’s Trade Commissioner hopes for the trade deal to “create a platform for working together to establish resilient and sustainable supply chains.” Additionally, through its Global Gateway initiative, the EU aims to compete with China’s BRI and gain more economic influence in Indonesia, pledging 2.4 bn EUR over the next three to five years to support Indonesia’s green transition.

Germany also emphasizes economic engagement with Indonesia: In 2023, German chancellor Scholz stressed that Indonesia represented an opportunity for German companies looking to diversify supply chains. At the same time, German economy minister Habeck announced the establishment of a joint economic and investment committee.

U.S. and European offers for engagement have been taken up by Jokowi but have not led to a significant break from China. On the contrary, Indonesia under Jokowi has doubled down on China economically. Will Prabowo, who won on the promise of continuing Jokowi policies, be more interested in diversification from China? How will Prabowo’s pre-election “anti-EU” rhetoric translate into his trade policies going forward?

Industrial policy: More controls on nickel and beyond?

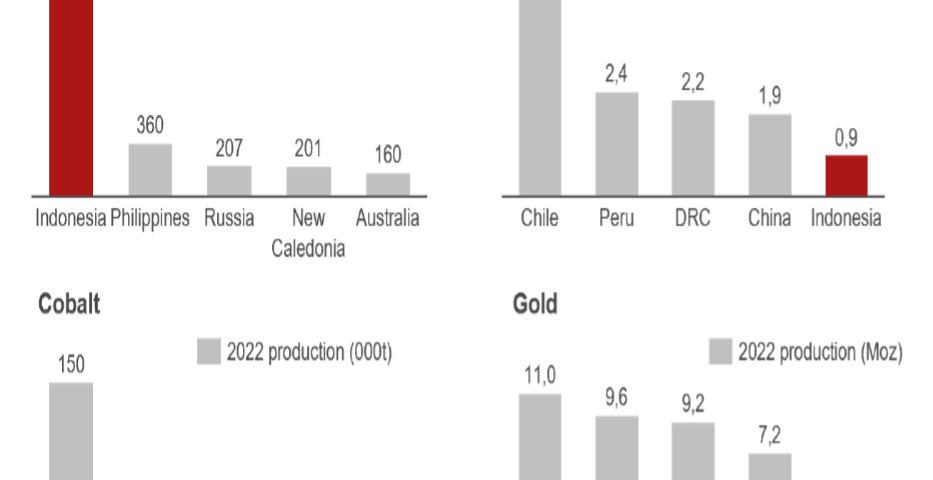

Indonesia is aware of the strategic importance of its rich mineral reserves. Indonesia accounts for around 42% of global nickel reserves and is the second largest supplier of cobalt, both of which are key inputs for the battery industry. Current President Jokowi has said that he hopes to leverage these resources to build an extended EV supply chain and transform the country into a global EV hub.

We will encourage our exports to no longer be in the form of commodities but in the form of semi-finished and finished goods.

The downstreaming policy has achieved some success. Following the ban of nickel in 2019, major EV and battery makers including Hyundai, LG, BYD and CATL have announced significant investments in the country. Tesla has also flirted with the idea of making inroads into Indonesia but so far nothing has happened. A significant barrier for U.S. companies is that Indonesia-based supply chains will inevitably include Chinese companies. This means EVs with Indonesian nickel will be excluded from US tax benefits.

The nickel ban has also led to WTO disputes between Indonesia and the EU. While the WTO upheld the EU claims that Indonesia’s ban violates trade rules, Indonesia refused to comply. Instead, Jokowi even extended the ban to bauxite (used for making aluminum).

Jokowi’s industrial policy approach to development is widely popular among Indonesians. Will Prabowo continue Jokowi’s approach to export bans and similar industrial policy tools? And how will he navigate the US-led mineral alliances to counter China going forward?

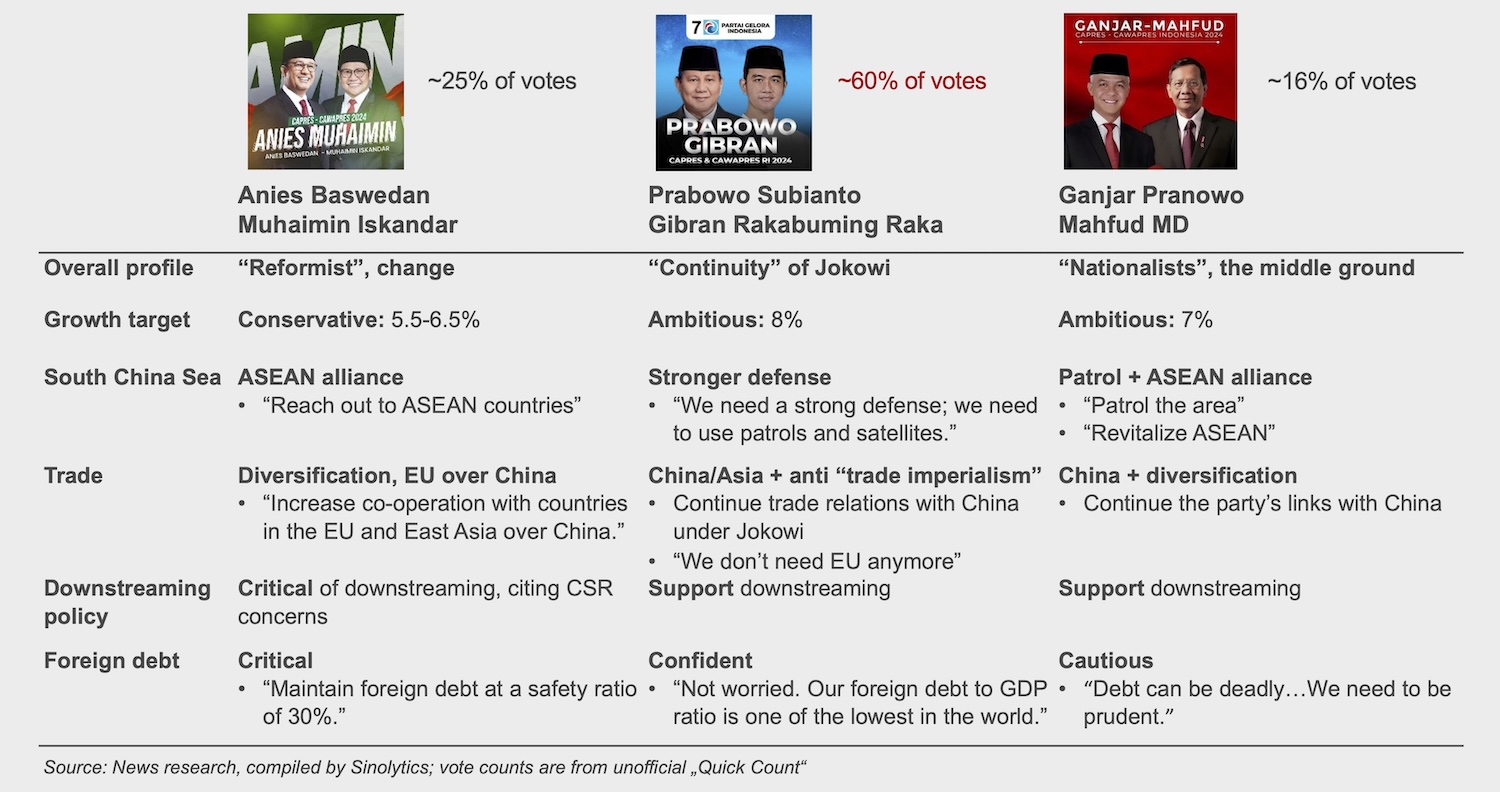

Political spectrum: Where Prabowo stands compared to his opponents

Among the three presidential candidates, the former Jakarta governor Anies Baswedan is the only one critical of Jokowi’s policies. He raised doubts on Jokowi’s billion-dollar project to build a new capital, pointed out the ESG concerns behind the industrial policies, and called for increased cooperation with the EU and other East Asian countries over China. The current estimates show Anies with around 25% of all votes, suggesting that the concerns about Jokowi’s policies are gaining traction in the political landscape of Indonesia. And it may grow bigger in the next election.

Among the three presidential candidates, the former Jakarta governor Anies Baswedan is the only one critical of Jokowi’s policies. He raised doubts on Jokowi’s billion-dollar project to build a new capital, pointed out the ESG concerns behind the industrial policies, and called for increased cooperation with the EU and other East Asian countries over China. The current estimates show Anies with around 25% of all votes, suggesting that the concerns about Jokowi’s policies are gaining traction in the political landscape of Indonesia. And it may grow bigger in the next election.

Both Prabowo (Gerindra party) and Ganjar (PDI-P party) vowed to continue Jokowi’s policies. Prabowo’s vice presidential running mate Gibran Rakabuming Raka is Jokowi’s eldest son, a choice that is widely believed to be a political deal and a silent nod from the current president.

But Prabowo also came with his own agenda. He called for increased military spending and showed more interest in engaging in international affairs. Despite a history of being blacklisted by the U.S. and Australia over human rights allegations, he managed to strengthen defense ties with Washington.

Coming from the same party as Jokowi, Ganjar's reservations about “foreign debt” (often communicated as a euphemism for China) suggested a more nuanced approach to China than Prabowo’s. Ganjar’s low vote share coupled with PDI-P’s parliamentary lead presents an intriguing dynamic going forward.

Geopolitics and security outlook

A more geopolitical Indonesia

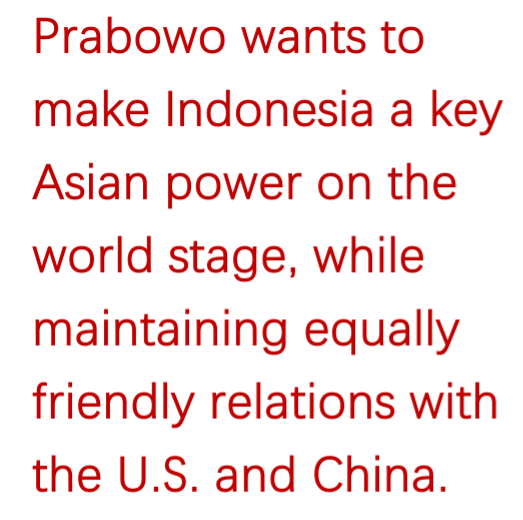

Prabowo will inherit a much more geopolitically divided world and a more prominent position for Indonesia in it.  While Prabowo mostly campaigned under the theme of continuity of Jokowi’s foreign policy, his temperamental and confrontational style will likely lead to subtle differences in approach to foreign policy. Furthermore, Prabowo has shown more interest in engaging in geopolitical topics than Jokowi and has promised on the campaign trail to make Indonesia a key Asian power on the world stage. His predecessor Jokowi famously never attended a UN General Assembly meeting.

While Prabowo mostly campaigned under the theme of continuity of Jokowi’s foreign policy, his temperamental and confrontational style will likely lead to subtle differences in approach to foreign policy. Furthermore, Prabowo has shown more interest in engaging in geopolitical topics than Jokowi and has promised on the campaign trail to make Indonesia a key Asian power on the world stage. His predecessor Jokowi famously never attended a UN General Assembly meeting.

The geopolitical dynamics, especially the U.S.-China rivalry, will present Prabowo with the perfect chance to play a more active role on the international stage. Prabowo has already made clear that he wants to continue engaging with China economically while deepening security ties with the U.S. This means he will likely continue an approach of non-alignment or balancing the two superpowers. From the view of both Beijing and Washington, Prabowo’s election is a mixed bag.

More security ties despite potential for democratic backsliding?

Even though he received a military education in the U.S., Prabowo’s human rights record under President Suharto has been a major problem in his relationship with the U.S. It was only in 2020, under the Trump administration, that the U.S. lifted his visa ban and engaged with him as Indonesia’s defense minister. While Prabowo has somewhat softened his public image, strongman and nationalistic rhetoric remained key elements of his campaign. This might explain why Washington has been slow in congratulating Prabowo on his likely electoral success. Concerns about democratic backsliding could become a point of contestation with the U.S. in the future. This will also depend on who will sit in the White House after 2024. A Trump administration will likely de-emphasize democratic values in its foreign policy.

Despite these frictions, Prabowo is likely to pursue closer security ties with Washington given that the U.S. views Indonesia as an indispensable partner in the region. Already during his time as defense minister, Prabowo was successful in securing U.S. security commitments, for example with the signing of the Defense Cooperation Arrangement and the increased sales of weapons.

Security risks over territorial disputes with China remain

From China’s perspective, Prabowo’s commitment to keeping Indonesia as a non-aligned country despite geopolitical pressures to choose sides is good news. During his tenure as defense minister Prabowo has also maintained friendly relations with China, meeting with Chinese counterparts on five occasions and trying to advance security dialogues such as the Defense Industry Cooperation Meeting. Furthermore, during the campaign, he has also assured that conflicts with China can be solved through dialogue. And given that Indonesia is not a claimant in the South China Sea, the risk for escalation with China is lower compared to other ASEAN nations such as Vietnam which do have claims.

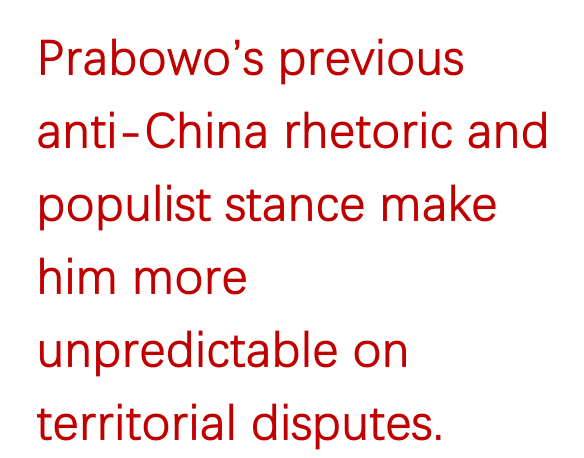

However, this has been a rather recent shift in Prabowo’s policy stance. In past elections, he adopted populist stances against China and has campaigned on a strong anti-China platform. His previous rhetoric on China and his off-the-cuff personality suggest that he may be somewhat more unpredictable than his predecessor. For instance, Jokowi was relatively restrained in 2021 when Chinese vessels entered Indonesia’s Exclusive Economic Zone in the Natuna Sea. As presidential candidate, Prabowo has argued that tensions in the South China Sea underline the need for a strong Indonesian defense force and additional capabilities to deter intrusions. Especially if public opinion turns negative on China (currently only 25% of Indonesians view China unfavorably), Prabowo might be tempted to revert back to nationalist rhetoric on territorial integrity to secure public support.

However, this has been a rather recent shift in Prabowo’s policy stance. In past elections, he adopted populist stances against China and has campaigned on a strong anti-China platform. His previous rhetoric on China and his off-the-cuff personality suggest that he may be somewhat more unpredictable than his predecessor. For instance, Jokowi was relatively restrained in 2021 when Chinese vessels entered Indonesia’s Exclusive Economic Zone in the Natuna Sea. As presidential candidate, Prabowo has argued that tensions in the South China Sea underline the need for a strong Indonesian defense force and additional capabilities to deter intrusions. Especially if public opinion turns negative on China (currently only 25% of Indonesians view China unfavorably), Prabowo might be tempted to revert back to nationalist rhetoric on territorial integrity to secure public support.

Trade and industrial policy outlook

China: A necessary entanglement

Prabowo’s stance on trade with China has also undergone a shift. During the 2019 election, he was much more critical of China, and pledged to review Chinese investments if he won. But after losing two times to Jokowi, Prabowo has adopted a more pragmatic development first approach. He promised an ambitious 8% growth target and campaigned on stronger welfare offers, including a $29 billion free lunch program. He also supported Jokowi’s infrastructure projects, including the $32 billion plan to build a new capital city from scratch.

All of this would require a strong economic relationship with China. Prabowo needs more trade and foreign investments to deliver his growth promises and likely won’t be picky about the source. China’s less ESG-stringent investments, coupled with concessional funding, as in the Jakarta-Bandung Highspeed Rail case, will be crucial to continuing Indonesia’s infrastructure projects in the pipeline.

The hard constraints that Prabowo may face are the budget, rising concerns about foreign debt and a necessary parliamentary approval to secure his pick of finance minister. The high-speed railway was financed in large part by a 40-year loan from China with interest rates up to 3.4%, making the $1.6 billion budget overrun, which Beijing refused to cover, more costly. Prabowo’s confident comments on debt – “I am not worried” – and growth promises conditioned on aggressive fiscal expansions have raised concerns about the country’s fiscal discipline among rating agencies. On the other hand, Beijing’s hardball positions on debt negotiations may strain bilateral economic relations and incentivize Indonesia to diversify infrastructure partners.

Anti-EU? Expect pragmatism with a nationalistic twist

While Prabowo is expected to continue Jokowi’s trade policies, he brings some uncertainty and a nationalistic bent to the table. In criticism of the EU’s import ban on Indonesian soy, palm oil, coffee and other products over deforestation concerns, Prabowo said that “we don’t need Europe anymore”. Instead, he called on Indonesia to rebalance by learning from its Asian neighbors including Japan, India and China rather than from the West. Indonesia has been active in shaping the implementation of RCEP, the ASEAN-plus-five trade pact. It will continue to pursue a leading role in regional trade integration.

Indonesia’s trade relations with the U.S. are less contentious than with the EU. While the U.S. is not happy about Indonesia’s nationalistic resource policies, it has not taken the issue to the WTO. But Washington’s insistence to include labor protections led to the stalling of IPEF negotiation. Indonesia rejected an enforceable system for labor standards while the other IPEF partners called for a different approach.

Prabowo did not seem to value diversification much in itself during the campaign, compared to his two contenders: Anies deliberately called to prioritize cooperation with the EU over China while Ganjar signaled more “wariness” of China dependencies. His sentiment of anti-“trade imperialism” may complicate future negotiations with the EU and the U.S. as they usually come with many strings attached.

Industrial policy: Friend shore or fence-sit?

Prabowo has repeatedly voiced support for Jokowi’s commodity downstreaming policies and promised more. He vowed to pursue downstream industrialization across 21 commodities, including coal, tin, copper, steel, gold, silver, asphalt, crude oil, natural gas, palm oil, and coconut. Expect more protectionist measures (e.g. export bans, negative investment lists) on critical raw materials under a Prabowo presidency. But their effect may be more limited than in the case of nickel. For example, the 2023 export ban on bauxite, intended to incentivize investment in the downstream sectors, raised doubts about its effectiveness, given Indonesia’s less dominant position in the output and a much higher starting cost than that for nickel smelters.

How Prabowo will deal with the extensive China footprint in Indonesia’s mineral supply chain is less clear and needs close monitoring going forward. As the EU and the U.S. are stepping up efforts to build a mineral security partnership to counter China’s dominance, Indonesia needs to find ways to circumvent restrictions or position itself as a credible neutral player to benefit from diversification incentives.

Jokowi has tried but failed to negotiate a more competitive entry for Indonesian nickel to the U.S. market when he met Biden in 2023. In the same visit, Jokowi also brought to the agenda a critical mineral partnership with the U.S. The Biden administration is weighing these deals over the lagging ESG standards in Indonesia, according to a government source. Prabowo will likely continue these efforts. Whether Indonesia can avoid being perceived as “choosing sides” in the competition for mineral alliance will depend on effective diplomacy and gaining an indispensable share of the global value chain.

What does this mean for your de-risking strategy: Opportunities with caveats?

Geopolitical risk hedging: Indonesia will assume more weight internationally, and it will stick to non-alignment

Indonesia will assume more geopolitical weight as a key “swing state” in the Asia Pacific. Multinational companies looking for promising markets to hedge China-related geopolitical risks need to pay close attention to how Indonesia’s next leader will navigate and shape the geopolitical dynamics in the region. As the geopolitical rivalry between China and the U.S. is likely to intensify, so will the pressure of both superpowers on Indonesia to more clearly position itself. However, if Indonesia manages to become an integral part of the global value chain, e.g. for the automotive industry, it will gain leverage vis-à-vis the U.S. and China. This could benefit Indonesia for example in negotiations over inclusion in the IRA. India, a country that Prabowo said that Indonesia should learn from, is an example of how it is possible to gain greater geopolitical weight while maintaining a relatively independent stance.

Political engagement: European policymakers will need to be ready for tough negotiations

For European policymakers, the new government comes with a chance to create new momentum for a free trade deal. However, political and economic compromises need to be built into any agreement. Prabowo expressed strong disapproval for the “Western” moralistic approach to development during his campaigns. While European values and standards should be reflected in trade agreements, policymakers need to balance the different priorities of weaning Indonesia off China’s economic sphere of influence versus living up to the high standards set for all of EU’s free trade agreements. For example, if the EU finds a way to compromise on its concerns over deforestation in Indonesia, the path towards an agreement would be made easier.

De-risking: More incentives for investment diversification, but China footprint hard to cut from supply chain

The EU and the U.S. are increasing economic engagement with Indonesia in the wake of China’s advancement in the country. This may lead to more incentives, trade facilitation and bilateral political and business exchanges, creating opportunities for multinational businesses to better understand and assess Indonesia’s potential for de-risking. For example, Indonesia’s Ministry of Investment is consulting their EU counterparts to launch an Indonesia-EU Investment Attraction Plan in 2024, focusing on EV, renewable energy, healthcare/pharma, electronics, transport/logistics and agribusiness, and pledging one-on-one business meetings.

This may lead to more incentives, trade facilitation and bilateral political and business exchanges, creating opportunities for multinational businesses to better understand and assess Indonesia’s potential for de-risking. For example, Indonesia’s Ministry of Investment is consulting their EU counterparts to launch an Indonesia-EU Investment Attraction Plan in 2024, focusing on EV, renewable energy, healthcare/pharma, electronics, transport/logistics and agribusiness, and pledging one-on-one business meetings.

The picture for supply chain de-risking is less clear. China’s dominance in Indonesia’s nickel outputs shows how difficult it is to cut China out of global supply chains. Businesses should invest in understanding local suppliers’ ownership structure and create transparency in the supply chain. Furthermore, businesses should stay up to date with relevant supply chain due diligence regulations to ensure compliance.

Nickel and beyond: Resource nationalism to continue, investment opportunities in the downstream

Prabowo made it clear that he will extend the downstreaming policies to more commodities, ranging from minerals to oil and gas, fishery to forestry. This will mean more protectionism and could disrupt access to strong>upstream inputs. On the other hand, it also brings investment opportunities and policy support to the downstream sectors for vertical integration and new market expansion. For example, Hyundai’s investment in Indonesia has made it a political showcase for Jokowi, who praised the company as a milestone in the country’s EV development. While its China market shares declined, Hyundai led Indonesia’s EV sales in 2023. From 2024 onwards, with locally produced battery in a plant jointly invested by LG, Hyundai will be able to increase its local content rate to around 60%, which brings tax incentives and additional subsidies. Besides EV, the country’s rich mineral reserves harbor similar potentials for other downstream products including solar panels, automotive components (tyres, bearings, etc.), chemicals, food and beverages.

Public communication: Better ESG, especially safety, standards

While Prabowo’s win seems to suggest that environmental and social issues are secondary to development, it is worth noting that the political voice promising better ESG standards is gaining traction, evidenced by Anies’ rise. Public concerns are growing over the deadly explosion at a Chinese-owned nickel plant last year. At a time of rising skepticism over the safety of Chinese plants, multinational companies can position themselves through better ESG standards to local governments and the public.

Business environment: Expect continued improvement, but some doubts about policy consistency and stability in the long run

There is still uncertainty about whether Prabowo will deliver his promises of “Jokowi 2.0”. If Prabowo’s government continues improving the business environment following Jokowi’s Omnibus Law, it will help enhance Indonesia’s attraction for foreign investment. But other more deep-rooted structural issues such as corruption and talent shortage will require time and consistent policy push to see meaningful progress and remain major impediments to Indonesia’s economy for now.

Furthermore, Prabowo’s authoritarian tendency and the “dynastic” politics of Jokowi raise doubts on the country’s long-term political stability. The incremental but worrying steps of democratic backsliding may lead to a murkier policymaking environment and compromised legislative processes, a key business risk that needs dedicated monitoring going forward.

Read the full report here. For further in-depth information contact the authors Jingwen Tong and Martin Catarata.